Favre averaged Navier-Stokes equations

From CFD-Wiki

m (fixed case on headings) |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | + | == Instantaneous equations == | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | <math> | + | The instantaneous continuity equation (1), momentum equation (2) and energy equation (3) for a compressible fluid can be written as: |

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"> | ||

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + | \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + | ||

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}\left[ \rho u_j \right] = 0 | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}\left[ \rho u_j \right] = 0 | ||

| - | </math> | + | </math> |

| - | + | </td><td width="5%">(1)</td></tr> | |

| - | <math> | + | <tr><td> |

| + | :<math> | ||

\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \rho u_i \right) + | \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \rho u_i \right) + | ||

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

\left[ \rho u_i u_j + p \delta_{ij} - \tau_{ji} \right] = 0 | \left[ \rho u_i u_j + p \delta_{ij} - \tau_{ji} \right] = 0 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | + | </td><td>(2)</td></tr> | |

| - | <math> | + | <tr><td> |

| + | :<math> | ||

\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \rho e_0 \right) + | \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \rho e_0 \right) + | ||

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

\left[ \rho u_j e_0 + u_j p + q_j - u_i \tau_{ij} \right] = 0 | \left[ \rho u_j e_0 + u_j p + q_j - u_i \tau_{ij} \right] = 0 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td>(3)</td></tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| - | For a Newtonian fluid, assuming Stokes Law for mono-atomic gases, the viscous | + | For a Newtonian fluid, assuming Stokes Law for mono-atomic gases, the viscous stress is given by: |

| - | stress is given by: | + | |

| - | <math> | + | <table width="100%"> |

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

\tau_{ij} = 2 \mu S_{ij}^* | \tau_{ij} = 2 \mu S_{ij}^* | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(4)</td></tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| - | Where the trace-less viscous strain-rate is defined | + | Where the trace-less viscous strain-rate is defined by: |

| - | by: | + | |

| - | <math> | + | <table width="100%"> |

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

S_{ij}^* \equiv | S_{ij}^* \equiv | ||

\frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{\partial u_i}{\partial x_j} + | \frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{\partial u_i}{\partial x_j} + | ||

| Line 36: | Line 46: | ||

\frac{1}{3} \frac{\partial u_k}{\partial x_k} \delta_{ij} | \frac{1}{3} \frac{\partial u_k}{\partial x_k} \delta_{ij} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(5)</td></tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

The heat-flux, <math>q_j</math>, is given by Fourier's law: | The heat-flux, <math>q_j</math>, is given by Fourier's law: | ||

| - | <math> | + | <table width="100%"> |

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

q_j = -\lambda \frac{\partial T}{\partial x_j} | q_j = -\lambda \frac{\partial T}{\partial x_j} | ||

\equiv -C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial T}{\partial x_j} | \equiv -C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial T}{\partial x_j} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(6)</td></tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| - | Where the laminar Prandtl number <math>Pr</math> is defined | + | Where the laminar Prandtl number <math>Pr</math> is defined by: |

| - | by: | + | |

| - | <math> | + | <table width="100%"> |

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

Pr \equiv \frac{C_p \mu}{\lambda} | Pr \equiv \frac{C_p \mu}{\lambda} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(7)</td></tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| - | To close these equations it is also necessary to specify an equation of state. | + | To close these equations it is also necessary to specify an equation of state. Assuming a calorically perfect gas the following relations are valid: |

| - | Assuming a calorically perfect gas the following relations are valid: | + | |

| - | <math> | + | <table width="100%"> |

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

\gamma \equiv \frac{C_p}{C_v} ~~,~~ | \gamma \equiv \frac{C_p}{C_v} ~~,~~ | ||

p = \rho R T ~~,~~ | p = \rho R T ~~,~~ | ||

| Line 60: | Line 80: | ||

C_p - C_v = R | C_p - C_v = R | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(8)</td></tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| - | Where <math>\gamma, C_p, C_v</math> and <math>R</math> are constant. | + | Where <math>\gamma</math>, <math>C_p</math>, <math>C_v</math> and <math>R</math> are constant. |

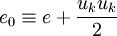

The total energy <math>e_0</math> is defined by: | The total energy <math>e_0</math> is defined by: | ||

| - | < | + | <table width="100%"> |

| - | <math> | + | <tr><td> |

| + | :<math> | ||

e_0 \equiv e + \frac{u_k u_k}{2} | e_0 \equiv e + \frac{u_k u_k}{2} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | </ | + | </td><td width="5%">(9)</td></tr> |

| + | </table> | ||

| - | Note that the | + | Note that the corresponding expression (15) for Favre averaged turbulent flows contains an extra term related to the turbulent energy. |

| - | corresponding expression | + | |

| - | for Favre averaged turbulent flows contains an | + | |

| - | extra term related to the turbulent energy. | + | |

| + | Equations (1)-(9), supplemented with gas data for <math>\gamma</math>, <math>Pr</math>, <math>\mu</math> and perhaps <math>R</math>, form a closed set of partial differential equations, and need only be complemented with boundary conditions. | ||

| + | == Favre averaged equations == | ||

| + | It is not possible to solve the instantaneous equations directly for most engineering applications. At the Reynolds numbers typically present in real cases these equations have very chaotic turbulent solutions, and it is necessary to model the influence of the smallest scales. Most turbulence models are based on one-point averaging of the instantaneous equations. The averaging procedure will be described in the following sections. | ||

| - | <math> | + | === Averaging === |

| + | |||

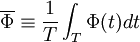

| + | Let <math>\Phi</math> be any dependent variable. It is convenient to define | ||

| + | two different types of averaging of <math>\Phi</math>: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Classical time averaging ([[Reynolds averaging]]): | ||

| + | <table width="100%"> | ||

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\overline{\Phi} \equiv \frac{1}{T} \int_T \Phi(t) dt</math> | ||

| + | </td> | ||

| + | <td rowspan="2" width="5%">(10)</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\Phi' \equiv \Phi - \overline{\Phi}</math> | ||

| + | </td></tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Density weighted time averaging ([[Favre averaging]]): | ||

| + | <table width="100%"> | ||

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\widetilde{\Phi} \equiv \frac{\overline{\rho \Phi}}{\overline{\rho}}</math> | ||

| + | </td><td rowspan="2" width="5%">(11)</td></tr> | ||

| + | <tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\Phi'' \equiv \Phi - \widetilde{\Phi}</math> | ||

| + | </td></tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note that with the above definitions <math>\overline{\Phi'} = 0</math>, but <math>\overline{\Phi''} \neq 0</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Open turbulent equations === | ||

| + | |||

| + | In order to obtain an averaged form of the governing equations, the instantaneous continuity equation (1), momentum | ||

| + | equation (2) and energy equation (3) are time-averaged. Introducing a density weighted time average decomposition (11) of <math>u_i</math> and <math>e_0</math>, and a standard time average decomposition (10) of <math>\rho</math> and <math>p</math> gives the following exact open equations: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

\frac{\partial \overline{\rho}}{\partial t} + | \frac{\partial \overline{\rho}}{\partial t} + | ||

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}\left[ \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right] = 0 | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}\left[ \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right] = 0 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(12)</td></tr></table> | ||

| - | <math> | + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> |

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right) + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | \left[ | ||

| + | \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{u_j} + \overline{p} \delta_{ij} + | ||

| + | \overline{\rho u''_i u''_j} - \overline{\tau_{ji}} | ||

| + | \right] | ||

| + | = 0 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(13)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{e_0} \right) + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | \left[ | ||

| + | \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_j} \widetilde{e_0} + | ||

| + | \widetilde{u_j} \overline{p} + \overline{u''_j p} + | ||

| + | \overline{\rho u''_j e''_0} + \overline{q_j} - \overline{u_i \tau_{ij}} | ||

| + | \right] | ||

| + | = 0 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(14)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

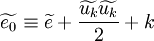

| + | The density averaged total energy <math>\widetilde{e_0}</math> is given by: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\widetilde{e_0} \equiv \widetilde{e} + \frac{\widetilde{u_k} \widetilde{u_k}}{2} + k</math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(15)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where the turbulent energy, <math>k</math>, is defined by: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>k \equiv \widetilde{\frac{u''_k u''_k}{2}}</math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(16)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Equation (12), (13) and (14) are referred to as the Favre averaged Navier-Stokes equations. <math>\overline{\rho}</math>, <math>\widetilde{u_i}</math> and <math>\widetilde{e_0}</math> are the primary solution variables. Note that this is an open set of partial differential equations that contains several unkown correlation terms. In order to obtain a closed form of equations that can be solver it is neccessary to model these unknown correlation terms. | ||

| + | |||

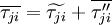

| + | === Approximations and modeling === | ||

| + | |||

| + | To analyze equation (12), (13) and (14) it is convenient to rewrite the unknown terms in the following way: | ||

| + | |||

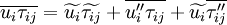

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\overline{\tau_{ji}} = \widetilde{\tau_{ji}} + \overline{\tau''_{ji}}</math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(17)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

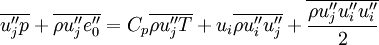

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\overline{u''_j p} + \overline{\rho u''_j e''_0} = | ||

| + | C_p \overline{\rho u''_j T} + | ||

| + | u_i \overline{\rho u''_i u''_j} + \overline{\frac{\rho u''_j u''_i u''_i}{2}} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(18)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

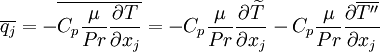

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\overline{q_j} = | ||

| + | - \overline{C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial T}{\partial x_j}} = | ||

| + | - C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j} - | ||

| + | C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial \overline{T''}}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(19)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math>\overline{u_i \tau_{ij}} = | ||

| + | \widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{\tau_{ij}} + \overline{u''_i \tau_{ij}} + \widetilde{u_i} \overline{\tau''_{ij}} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(20)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where the perfect gas relations (8) and Fourier's law (6) have been used. Note also that fluctuations in the molecular viscosity, <math>\mu</math>, have been neglected. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Inserting (17)-(20) into (12), (13) and (14) gives: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \frac{\partial \overline{\rho}}{\partial t} + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}\left[ \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right] = 0 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(21)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right) + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | \left[ | ||

| + | \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{u_j} + \overline{p} \delta_{ij} + | ||

| + | \underbrace{\overline{\rho u''_i u''_j}}_{(1^*)} - \widetilde{\tau_{ji}} - | ||

| + | \underbrace{\overline{\tau''_{ji}}}_{(2^*)} | ||

| + | \right] | ||

| + | = 0 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(22)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial t} | ||

| + | \left(\overline{\rho} \widetilde{e_0} \right) + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | [ | ||

| + | \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_j} \widetilde{e_0} + | ||

| + | \widetilde{u_j} \overline{p} + | ||

| + | \underbrace{C_p \overline{\rho u''_j T}}_{(3^*)} + | ||

| + | \underbrace{\widetilde{u_i} \overline{\rho u''_i u''_j}}_{(4^*)} + | ||

| + | \underbrace{\overline{\frac{\rho u''_j u''_i u''_i}{2}}}_{(5^*)} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td></tr><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | - C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | - \underbrace{C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial \overline{T''}} | ||

| + | {\partial x_j}}_{(6^*)}- | ||

| + | \widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{\tau_{ij}} - | ||

| + | \underbrace{\overline{u''_i \tau_{ij}}}_{(7^*)} - | ||

| + | \underbrace{\widetilde{u_i} \overline{\tau''_{ij}}}_{(8^*)} | ||

| + | ] | ||

| + | = 0 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%" rowspan="2">(23)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The terms marked with <math>(1^*)-(8^*)</math> are unknown, and have to be modeled in some way. | ||

| + | |||

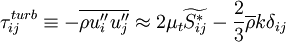

| + | Term <math>(1^*)</math> and <math>(4^*)</math> can be modeled using an eddy-viscosity assumption for the Reynolds stresses, <math>\tau_{ij}^{turb}</math>: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \tau_{ij}^{turb} \equiv | ||

| + | - \overline{\rho u''_i u''_j} \approx | ||

| + | 2 \mu_t \widetilde{S_{ij}^*} - | ||

| + | \frac{2}{3} \overline{\rho} k \delta_{ij} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(24)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where <math>\mu_t</math> is a turbulent viscosity, which is estimated with a turbulence model. The last term is included in order to ensure that the trace of the Reynolds stress tensor is equal to <math>-2 \rho k</math>, as it should be. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Term <math>(2^*)</math> and <math>(8^*)</math> can be neglected if: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \left| \widetilde{\tau_{ij}} \right| >> | ||

| + | \left| \overline{\tau''_{ij}} \right| | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(25)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is true for virtually all flows. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Term <math>(3^*)</math>, corresponding to turbulent transport of heat, can be modeled using a gradient approximation for the turbulent heat-flux: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | q_j^{turb} \equiv | ||

| + | C_p \overline{\rho u''_j T} \approx | ||

| + | - C_p \frac{\mu_t}{Pr_t} \frac{\partial \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(26)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where <math>Pr_t</math> is a turbulent Prandtl number. Often a constant <math>Pr_t \approx 0.9</math> is used. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Term <math>(5^*)</math> and <math>(7^*)</math>, corresponding to turbulent transport and molecular diffusion of turbulent energy, can be neglected if the turbulent energy is small compared to the enthalpy: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | k << \widetilde{h} = C_p \widetilde{T} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(27)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is a reasonable approximation for most flows below the hyper-sonic regime. A better approximation might be a gradient expression of the form: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \overline{\frac{\rho u''_j u''_i u''_i}{2}} - | ||

| + | \overline{u''_i \tau_{ij}} \approx | ||

| + | - \left( \mu + \frac{\mu_t}{\sigma_k} \right) \frac{\partial k}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(28)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where <math>\sigma_k</math> is a model constant. This approximation will not be included in the derived formulas below. Instead term <math>(5^*)</math> and <math>(7^*)</math> will be set to zero in the energy equation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Term <math>(6^*)</math> is an artifact from the Favre averaging. It is related to heat conduction effects associated with temperature fluctuations.It can be be neglected if: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \left| \frac{\partial^2 \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j^2} \right| >> | ||

| + | \left| \frac{\partial^2 \overline{T''}}{\partial x_j^2} \right| | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(29)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is true for virtually all flows, and has been assumed in all follwing equations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Closed approximated equations === | ||

| + | |||

| + | To summarize, the governing equations (21)-(23), with assumptions (24), (25), (26), (27) and (29) can be written as in (30)-(39). These equations are valid for a perfect gas. Note also that all fluctuations in the molecular viscosity have been neglected. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \frac{\partial \overline{\rho}}{\partial t} + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}\left[ \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right] = 0 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(30)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right) + | \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right) + | ||

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

| Line 94: | Line 352: | ||

= 0 | = 0 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(31)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{e_0} \right) + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | \left[ | ||

| + | \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_j} \widetilde{e_0} + | ||

| + | \widetilde{u_j} \overline{p} + | ||

| + | \widetilde{q_j^{tot}} - | ||

| + | \widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{\tau_{ij}^{tot}} | ||

| + | \right] = 0 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(32)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \widetilde{\tau_{ij}^{tot}} \equiv \widetilde{\tau_{ij}^{lam}} + \widetilde{\tau_{ij}^{turb}} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </td><td width="5%">(33)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \widetilde{\tau_{ij}^{lam}} \equiv | ||

| + | \widetilde{\tau_{ij}} = | ||

| + | \mu | ||

| + | \left( | ||

| + | \frac{\partial \widetilde{u_i} }{\partial x_j} + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial \widetilde{u_j} }{\partial x_i} - | ||

| + | \frac{2}{3} \frac{\partial \widetilde{u_k} }{\partial x_k} \delta_{ij} | ||

| + | \right) | ||

| + | </math></td><td width="5%">(34)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \widetilde{\tau_{ij}^{turb}} \equiv | ||

| + | - \overline{\rho u''_i u''_j} \approx | ||

| + | \mu_t | ||

| + | \left( | ||

| + | \frac{\partial \widetilde{u_i} }{\partial x_j} + | ||

| + | \frac{\partial \widetilde{u_j} }{\partial x_i} - | ||

| + | \frac{2}{3} \frac{\partial \widetilde{u_k} }{\partial x_k} \delta_{ij} | ||

| + | \right) - | ||

| + | \frac{2}{3} \overline{\rho} k \delta_{ij} | ||

| + | </math></td><td width="5%">(35)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \widetilde{q_j^{tot}} \equiv \widetilde{q_j^{lam}} + \widetilde{q_j^{turb}} | ||

| + | </math></td><td width="5%">(36)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \widetilde{q_j^{lam}} \equiv | ||

| + | \widetilde{q_j} \approx | ||

| + | - C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j} = | ||

| + | - \frac{\gamma}{\gamma-1} \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | \left[ \frac{\overline{p}}{\overline{\rho}} \right] | ||

| + | </math></td><td width="5%">(37)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \widetilde{q_j^{turb}} \equiv | ||

| + | C_p \overline{\rho u''_j T} \approx | ||

| + | - C_p \frac{\mu_t}{Pr_t} \frac{\partial \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j} = | ||

| + | - \frac{\gamma}{\gamma-1} \frac{\mu_t}{Pr_t} \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} | ||

| + | \left[ \frac{\overline{p}}{\overline{\rho}} \right] | ||

| + | </math></td><td width="5%">(38)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

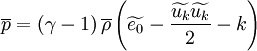

| + | <table width="100%"><tr><td> | ||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \overline{p} = \left( \gamma - 1 \right) \overline{\rho} | ||

| + | \left( \widetilde{e_0} - \frac{\widetilde{u_k} \widetilde{u_k}}{2} - k \right) | ||

| + | </math></td><td width="5%">(39)</td></tr></table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | If a separate turbulence model is used to calculate <math>\mu_t</math>, <math>k</math> and <math>Pr_t</math>, and gas data is given for <math>\mu</math>, <math>\gamma</math> and <math>Pr</math> these equations form a closed set of partial differential equations, which can be solved numerically. | ||

| - | |||

| - | [[Category:Fluid | + | [[Category:Fluid dynamics]][[Category:Equations]] |

Latest revision as of 20:33, 24 November 2005

Contents |

Instantaneous equations

The instantaneous continuity equation (1), momentum equation (2) and energy equation (3) for a compressible fluid can be written as:

|

| (1) |

|

| (2) |

|

| (3) |

For a Newtonian fluid, assuming Stokes Law for mono-atomic gases, the viscous stress is given by:

|

| (4) |

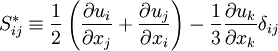

Where the trace-less viscous strain-rate is defined by:

|

| (5) |

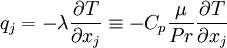

The heat-flux,  , is given by Fourier's law:

, is given by Fourier's law:

|

| (6) |

Where the laminar Prandtl number  is defined by:

is defined by:

|

| (7) |

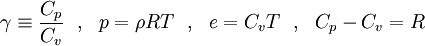

To close these equations it is also necessary to specify an equation of state. Assuming a calorically perfect gas the following relations are valid:

|

| (8) |

Where  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are constant.

are constant.

The total energy  is defined by:

is defined by:

|

| (9) |

Note that the corresponding expression (15) for Favre averaged turbulent flows contains an extra term related to the turbulent energy.

Equations (1)-(9), supplemented with gas data for  ,

,  ,

,  and perhaps

and perhaps  , form a closed set of partial differential equations, and need only be complemented with boundary conditions.

, form a closed set of partial differential equations, and need only be complemented with boundary conditions.

Favre averaged equations

It is not possible to solve the instantaneous equations directly for most engineering applications. At the Reynolds numbers typically present in real cases these equations have very chaotic turbulent solutions, and it is necessary to model the influence of the smallest scales. Most turbulence models are based on one-point averaging of the instantaneous equations. The averaging procedure will be described in the following sections.

Averaging

Let  be any dependent variable. It is convenient to define

two different types of averaging of

be any dependent variable. It is convenient to define

two different types of averaging of  :

:

- Classical time averaging (Reynolds averaging):

|

|

(10) |

|

|

- Density weighted time averaging (Favre averaging):

|

| (11) |

|

|

Note that with the above definitions  , but

, but  .

.

Open turbulent equations

In order to obtain an averaged form of the governing equations, the instantaneous continuity equation (1), momentum

equation (2) and energy equation (3) are time-averaged. Introducing a density weighted time average decomposition (11) of  and

and  , and a standard time average decomposition (10) of

, and a standard time average decomposition (10) of  and

and  gives the following exact open equations:

gives the following exact open equations:

|

| (12) |

|

| (13) |

|

| (14) |

The density averaged total energy  is given by:

is given by:

|

| (15) |

Where the turbulent energy,  , is defined by:

, is defined by:

|

| (16) |

Equation (12), (13) and (14) are referred to as the Favre averaged Navier-Stokes equations.  ,

,  and

and  are the primary solution variables. Note that this is an open set of partial differential equations that contains several unkown correlation terms. In order to obtain a closed form of equations that can be solver it is neccessary to model these unknown correlation terms.

are the primary solution variables. Note that this is an open set of partial differential equations that contains several unkown correlation terms. In order to obtain a closed form of equations that can be solver it is neccessary to model these unknown correlation terms.

Approximations and modeling

To analyze equation (12), (13) and (14) it is convenient to rewrite the unknown terms in the following way:

|

| (17) |

|

| (18) |

|

| (19) |

|

| (20) |

Where the perfect gas relations (8) and Fourier's law (6) have been used. Note also that fluctuations in the molecular viscosity,  , have been neglected.

, have been neglected.

Inserting (17)-(20) into (12), (13) and (14) gives:

|

| (21) |

|

| (22) |

|

| |

|

| (23) |

The terms marked with  are unknown, and have to be modeled in some way.

are unknown, and have to be modeled in some way.

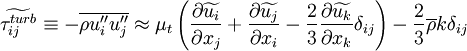

Term  and

and  can be modeled using an eddy-viscosity assumption for the Reynolds stresses,

can be modeled using an eddy-viscosity assumption for the Reynolds stresses,  :

:

|

| (24) |

Where  is a turbulent viscosity, which is estimated with a turbulence model. The last term is included in order to ensure that the trace of the Reynolds stress tensor is equal to

is a turbulent viscosity, which is estimated with a turbulence model. The last term is included in order to ensure that the trace of the Reynolds stress tensor is equal to  , as it should be.

, as it should be.

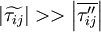

Term  and

and  can be neglected if:

can be neglected if:

|

| (25) |

This is true for virtually all flows.

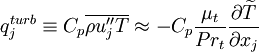

Term  , corresponding to turbulent transport of heat, can be modeled using a gradient approximation for the turbulent heat-flux:

, corresponding to turbulent transport of heat, can be modeled using a gradient approximation for the turbulent heat-flux:

|

| (26) |

Where  is a turbulent Prandtl number. Often a constant

is a turbulent Prandtl number. Often a constant  is used.

is used.

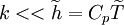

Term  and

and  , corresponding to turbulent transport and molecular diffusion of turbulent energy, can be neglected if the turbulent energy is small compared to the enthalpy:

, corresponding to turbulent transport and molecular diffusion of turbulent energy, can be neglected if the turbulent energy is small compared to the enthalpy:

|

| (27) |

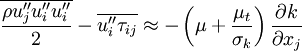

This is a reasonable approximation for most flows below the hyper-sonic regime. A better approximation might be a gradient expression of the form:

|

| (28) |

Where  is a model constant. This approximation will not be included in the derived formulas below. Instead term

is a model constant. This approximation will not be included in the derived formulas below. Instead term  and

and  will be set to zero in the energy equation.

will be set to zero in the energy equation.

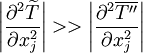

Term  is an artifact from the Favre averaging. It is related to heat conduction effects associated with temperature fluctuations.It can be be neglected if:

is an artifact from the Favre averaging. It is related to heat conduction effects associated with temperature fluctuations.It can be be neglected if:

|

| (29) |

This is true for virtually all flows, and has been assumed in all follwing equations.

Closed approximated equations

To summarize, the governing equations (21)-(23), with assumptions (24), (25), (26), (27) and (29) can be written as in (30)-(39). These equations are valid for a perfect gas. Note also that all fluctuations in the molecular viscosity have been neglected.

|

| (30) |

|

| (31) |

|

| (32) |

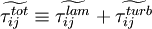

Where

|

| (33) |

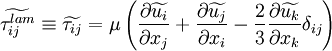

|

| (34) |

|

| (35) |

|

| (36) |

|

| (37) |

|

| (38) |

|

| (39) |

If a separate turbulence model is used to calculate  ,

,  and

and  , and gas data is given for

, and gas data is given for  ,

,  and

and  these equations form a closed set of partial differential equations, which can be solved numerically.

these equations form a closed set of partial differential equations, which can be solved numerically.

![\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}\left[ \rho u_j \right] = 0](/W/images/math/0/7/1/071e4f5508fd336ddad848551ce3188e.png)

![\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \rho u_i \right) +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[ \rho u_i u_j + p \delta_{ij} - \tau_{ji} \right] = 0](/W/images/math/6/f/c/6fc8041faa4be98ee72ec1e670fb22c7.png)

![\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \rho e_0 \right) +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[ \rho u_j e_0 + u_j p + q_j - u_i \tau_{ij} \right] = 0](/W/images/math/8/1/7/8176cdf87a72617542883cbbeafc50cc.png)

![\frac{\partial \overline{\rho}}{\partial t} +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}\left[ \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right] = 0](/W/images/math/d/c/d/dcd521718edfb790fcf5915dfff51dde.png)

![\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right) +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[

\overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{u_j} + \overline{p} \delta_{ij} +

\overline{\rho u''_i u''_j} - \overline{\tau_{ji}}

\right]

= 0](/W/images/math/8/b/6/8b6ccd8ae759989435f91b921c8f73b1.png)

![\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{e_0} \right) +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[

\overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_j} \widetilde{e_0} +

\widetilde{u_j} \overline{p} + \overline{u''_j p} +

\overline{\rho u''_j e''_0} + \overline{q_j} - \overline{u_i \tau_{ij}}

\right]

= 0](/W/images/math/1/e/5/1e51a93eafbd4986d688c8b17b5cb4dd.png)

![\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right) +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[

\overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{u_j} + \overline{p} \delta_{ij} +

\underbrace{\overline{\rho u''_i u''_j}}_{(1^*)} - \widetilde{\tau_{ji}} -

\underbrace{\overline{\tau''_{ji}}}_{(2^*)}

\right]

= 0](/W/images/math/0/c/1/0c1b4f5f40696025d26ab8a4f9aab2ab.png)

![- C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j}

- \underbrace{C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial \overline{T''}}

{\partial x_j}}_{(6^*)}-

\widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{\tau_{ij}} -

\underbrace{\overline{u''_i \tau_{ij}}}_{(7^*)} -

\underbrace{\widetilde{u_i} \overline{\tau''_{ij}}}_{(8^*)}

]

= 0](/W/images/math/d/d/0/dd02145b9c12b0593a92b6111faf8b17.png)

![\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_i} \right) +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[

\overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_j} \widetilde{u_i}

+ \overline{p} \delta_{ij}

- \widetilde{\tau_{ji}^{tot}}

\right]

= 0](/W/images/math/c/9/f/c9fb98d7716cc9a91f7e78b0ed597728.png)

![\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left( \overline{\rho} \widetilde{e_0} \right) +

\frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[

\overline{\rho} \widetilde{u_j} \widetilde{e_0} +

\widetilde{u_j} \overline{p} +

\widetilde{q_j^{tot}} -

\widetilde{u_i} \widetilde{\tau_{ij}^{tot}}

\right] = 0](/W/images/math/5/1/f/51f2b9e686b9bc3d12de61fd9ce18d6b.png)

![\widetilde{q_j^{lam}} \equiv

\widetilde{q_j} \approx

- C_p \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j} =

- \frac{\gamma}{\gamma-1} \frac{\mu}{Pr} \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[ \frac{\overline{p}}{\overline{\rho}} \right]](/W/images/math/c/1/8/c186ac9836f5861e9f44e8e110b3ee53.png)

![\widetilde{q_j^{turb}} \equiv

C_p \overline{\rho u''_j T} \approx

- C_p \frac{\mu_t}{Pr_t} \frac{\partial \widetilde{T}}{\partial x_j} =

- \frac{\gamma}{\gamma-1} \frac{\mu_t}{Pr_t} \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}

\left[ \frac{\overline{p}}{\overline{\rho}} \right]](/W/images/math/f/4/6/f46efa91ac350b21bd7d263841ed39f0.png)